Trawling Bulldozes the Ocean, Threatening Small Fisheries and the Environment

Published on The Associated Press.

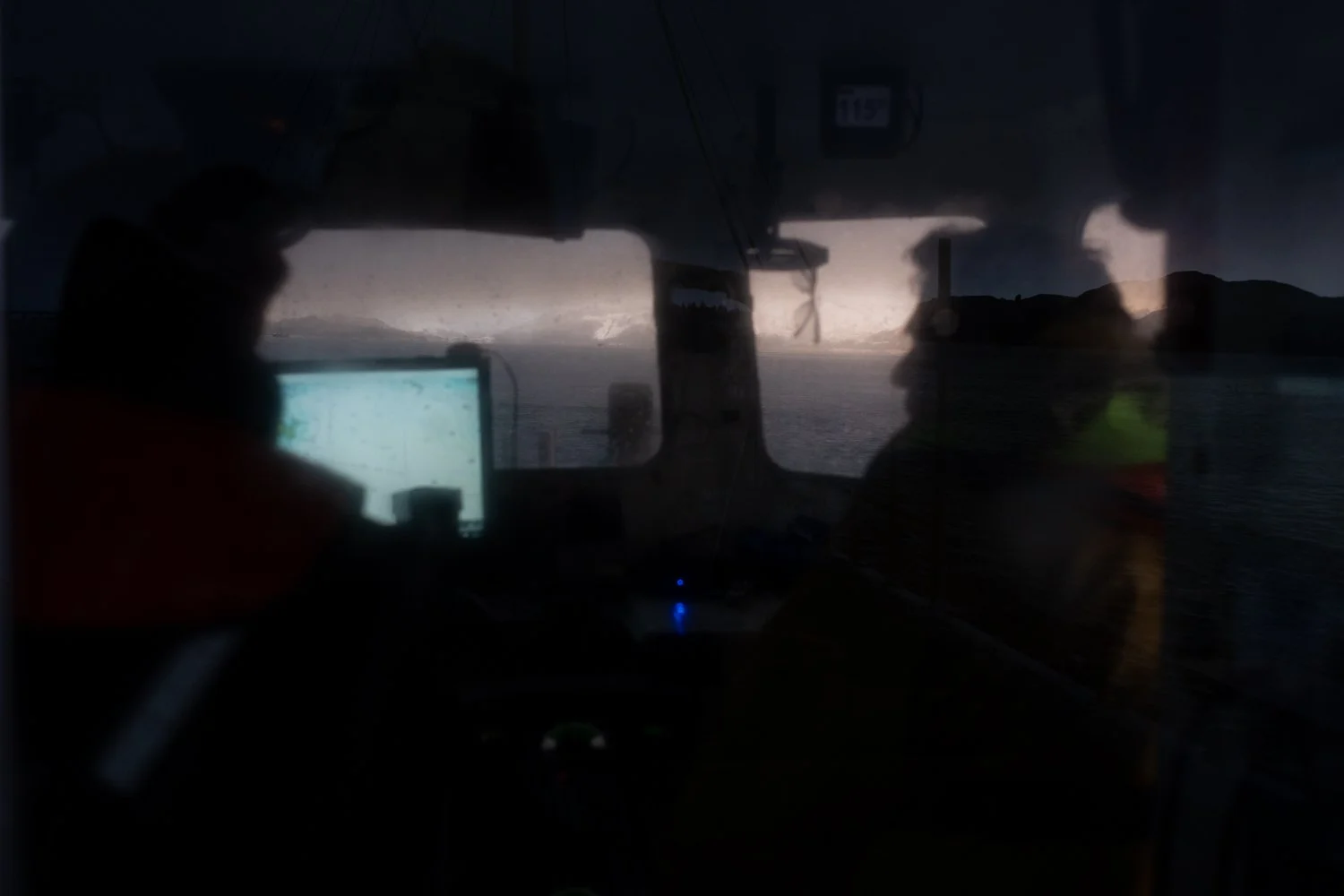

At dawn on a chilly November morning on the Isle of Skye, Bally Philp takes his creel fishing boat out for a long day. Snow has already covered the hills surrounding Loch Alsh and the Inner Sound where he does much of his work. As a Marine Protected Area (MPA) with management, Loch Alsh is one of few lochs in Scotland that prohibits detrimental methods of fishing such as bottom trawling and scallop dredging making it one of the healthiest ecosystems for fishing.

However, although 37% of Scotland’s waters have been designated as MPAs, only 3% have management measures to ensure that protection.

Right now, trawling and dredging is legal in most of Scotland’s coastline which has caused seabeds to be raked dry and fish stocks to collapse. Philp says, “The inshore archipelagos in the West Coast of Scotland used to be full of fish. We have no commercial fish left inshore at all.”

Bally Philp fishes in Loch Alsh off the coast of Kyleakin, Scotland.

Bally Philp stores fresh-caught prawns which are later delivered to buyer alive.

A starfish is returned to the sea. Any small amounts of bycatch are tossed back into the loch when caught by creel fisheries and the majority survives.

Creel fishing boats, tour boats, and others dock at the harbor in Portree, Scotland.

Marine biologist Caitlin Turner said the habitat destruction creates cascading effects throughout the ecosystem.

Fishermen dock a trawler that operates in the North Sea in Fraserburgh, a fishing town in northeastern Scotland.

Birds fly over the small fishing town of Kyleakin, Scotland in the early morning.

A crew member on Bally Philp's creel fishing boat returns the prepared creels back into the loch.

Ropes are tied to the side of a small-scale creel fishing vessel used to attach the creels to one another and to the buoy.

Bally Philp looks out at the loch for the buoy marking his creels in Loch Alsh in Scotland.

Bally Philp and his crew member take the boat out to their creels in Loch Alsh.

Extra shells from scallops are stored at Keltic Seafare in Dingwall, Scotland.

An employee at Keltic Seafare takes live prawns received from a fishery and weighs them before packing them for export in Dingwall, UK.

A creel is pulled up from the loch.

Seagulls fly near a creel fishing vessel on Loch Alsh.

A crew member on Bally Philp’s boat puts new bait into the creels before resetting them into the loch.

The Chris Andra is a large trawling vessel docked in Fraserburgh, Scotland.

Kyleakin is a small town next to the Skye Bridge that's home to many sustainable fisheries, especially those who do creel fishing.

Alasdair Hughson is the owner of Keltic Seafare, a company that process sustainably caught prawns, lobsters, and scallops.

The vast majority of reefs in the UK have been lost. Loch Alsh has some of the most intact remaining.

A crew member on Bally Philp’s boat stores prawns.

A view from the northern coast of the Isle of Skye in Culnacnoc, Scotland.

Small-scale creel fishermen operate in Loch Alsh.

Many coastal regions in Scotland are susceptible to practices like bottom trawling and scallop dredging — so much so that the vast majority of biogenic reefs in the UK and Scotland have been lost. Loch Alsh has some of the most intact remaining.

In 1984, a limit prohibiting bottom-trawling in all waters within three miles from the Scottish shore was abolished, and since then, coastal communities have seen fish catches decline and seabed habitats become decimated. This has created a crisis for small town fisheries.

Philp continues, “We’ve gone from a fishing culture in Scotland where maybe eighty years ago there were 20,000 fishermen catching herring, cod, or those kinds of things to now there’s not a single fisherman employed in Scotland’s inshore waters who's actually catching fish.”

This leaves small town fisheries with few options: to relocate to the few MPAs with management, live nomadically to access the remaining catches needed, or abandon their businesses.

Alasdair Hughson is the owner of Keltic Seafare, a company that processes sustainably caught prawns, lobsters, and scallops. As a scallop diver himself, he's been forced to work an itinerant lifestyle. Although he has two children near Inverness, he spends four days a week at sea because many regions closer to the coast have been too degraded. He says, "If there was no need to increase the size of vessels and move about and become more nomadic, we would have just stayed the way we were."

"Fishers [were at] such a low ebb, the stock just wasn’t there. It was gone and it wasn’t regenerating because scallop dredging had altered the habitat to such an extent. Scallops need something to attach to and if you remove everything that sticks up from the seabed, they’re not going to come back."

His company services 40% of the Michelin restaurants in London, but profitability is still tight. Hughson hopes for further marine protection in Scotland's seas.

Most small-scale fisheries such as creel fishing are sustainable because they don’t harm the life and they return any unnecessary extra catch to the sea — most of this marine life survives. In contrast, the bycatch from bottom trawling can be more than 55% of their catch and rarely does any survive.

These small fisheries are forced to work harder to maintain their way of life, and the economy beyond these communities is also at risk.

The Economic Cost of Trawling

Small-scale fisheries also generate three to four times more jobs than industrial trawlers which suppress employment opportunities. For every trawler, four to five creel fishermen could be employed with less seabed disturbance and bycatch, and any catch from a creel fishery is worth a up to 5x as much as that from a trawler. In the past decade, many small-scale fisheries have closed because operational costs have gotten so high.

Philp says, “You’re forfeiting huge amounts of revenue [and] jobs, [and] you have a far higher ecological impact than is necessary to support those jobs and extract that resource.”

The threat to the livelihood of small-scale fisheries is not just a problem in Scotland. In England, the small-scale fleet is declining faster than ever and in Europe this is true as well.

Seafood restaurant owners also face steep prices for hand dived scallops and they worry about the future supply of seafood because of overfishing and degraded habitats. Brexit has also caused the availability and quality of certain foods to take a nose dive. Many restaurants want to operate more sustainably but are unable to. The chef at a seafood restaurant on the Isle of Skye, says, “There is a huge demand from tourists and it is difficult to meet these demands. I have noticed it get incrementally harder in the last eight years.”

Trawling in European waters also imposes up to €10.8 billion in annual costs to society — mostly from releasing carbon emissions when seabed sediments are disturbed. It’s only economically viable in the UK because of government fuel subsidies. And yet, banning bottom trawling in UK offshore protected areas could be worth over £3 billion to the economy over the next 20 years.

Scottish seafood is revered as some of the best in the world, but many people are not aware of the methods being used, the footprint they have, and how the industry is at risk. Without further restrictions, the options for buying a high-quality product that protects the environment and ensures the welfare of small communities are scarce. Overfishing is particularly causing a disaster for species such as North Sea cod which are at a crisis point now. Scotland is just one example of a widespread issue as this destructive fishing method is practiced globally.

Upcoming Government Impact

Philp says the only reason trawlers are so active is because they have the lobby power: “There are full-time lobbyists wandering around the halls of power pulling the shirt strings of Parliamentarians and saying we’re the economic powerhouse of the fishing industry.”

The Scottish government committed to beginning a consultation on fisheries management measures in inshore MPAs and Priority Marine Features before the end of 2025, but in December, it was announced that the consultation would be delayed by at least six months with implementation likely not beginning until the first half of 2027.

Conservationists are outraged by the delay on an issue that is causing harm to their communities and Scotland’s marine life. Organizations such as the Our Seas Coalition are holding meetings with industry representatives from all over Scotland.

Caitlin Turner, a marine biologist, advocates for healthier seas and against bottom trawling and scallop dredging. She argues that these methods of overfishing impact larger marine life as well: "If you degrade the habitat then there’s less places for juvenile fish to live and spawn in. This affects the abundance of the animals in the area. It trickles upwards, [and you’ll] have less of the bigger animals that feed on the prey animals ... Tourism could [also] eventually take a hit. It’s a massive source of income. Big fisheries are shooting themself in the foot."

When the consultation does occur, the Scottish government has an opportunity to act. It’s a critical moment for the restoration of the seas and the welfare of coastal communities. Scientists and community groups are in the field already designing new approaches to restoration such as restoring seagrass and oyster populations. But conservationists say this won’t be sufficient to protect the seas and their hope is for the reinstating of a coastal limit that protects at least 30% of Scotland inshore seas.

Many European countries are looking at one another right now, trying to tackle the issue of overfishing and figure out if they can still reach the 30x30 target. Philp believes that even if all of Scotland’s MPAs and Priority Marine Features are closed to trawling and dredging, they’ll still be far short of the target aiming to protect 30% of land and sea by 2030.

England recently had a similar consultation and we await the results. How Scotland and England decide to proceed will likely set the tone and level of ambition for the EU and arguably the combined outcomes of the UK and EU processes will set the tone for much of the world.

This is all happening in the backdrop of a movement of small-scale fisheries across the UK, Ireland, and mainland Europe demanding better protection of both the environment and the small-scale fishing fleet. The decisions taken in the year ahead will likely determine the future of Europe's seas.

Text and photographs are by Emily Whitney. To learn more about the impact of bottom trawling, watch Ocean with David Attenborough.